Brussels – It was only a matter of hours. No last-minute surprise, no challenge of two (or more) to lead the European Socialists in the June elections. The current European Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights, Nicolas Schmit, is the only name on the list to become the Spitzenkandidat of the Party of European Socialists (PES). This was announced today (Jan. 18) by the ad hoc working group of the PES, after the deadline for submitting nominations expired. “I confirm that Nicolas Schmit has met the necessary criteria to run as a common candidate of the ESP for the presidency of the European Commission,” the secretary general of the family of European Socialists, Giacomo Filibeck, announced in a note.

Schmit was nominated by the Luxembourg Socialist Workers Party (LSAP) and “widely supported” by the member parties of the PES. According to the internal rules, each candidate or nominee needs the support of at least nine full-member parties or organizations (i.e., 25 per cent of the total), with one nominating them and eight others supporting them. Official validation by the PES presidency is expected next week, after which, at the Electoral Congress scheduled for March 2 in Rome, Schmit “will be presented to be elected as a common candidate, kicking off the campaign for the 2024 European elections. “A longtime Luxembourg politician, Commissioner Schmit (who is expected to resign from the European Commission to focus on the election campaign) is singled out by his political family as a candidate “in favour of a stronger Europe that defends its values against the resurgence of the far right” with some aces up his sleeve: “Quality jobs, tax justice, affordable housing, and good public services for all.” And above all, a “more sustainable Europe, based on a socially equitable European Green Deal and an innovative and inclusive green and digital economy.” Reached by Eunews In recent days, the head of the Italian Democratic Party’s delegation to the European Parliament, Brando Benifei, had expressed “appreciation” for Schmit’s work “on a personal level.” The option is also seen “favourably” because of his portfolio of expertise in the von der Leyen cabinet: “He would adequately represent the commitment to a social Europe,” pending the decision to be made “as a whole political force” at the Rome Congress.

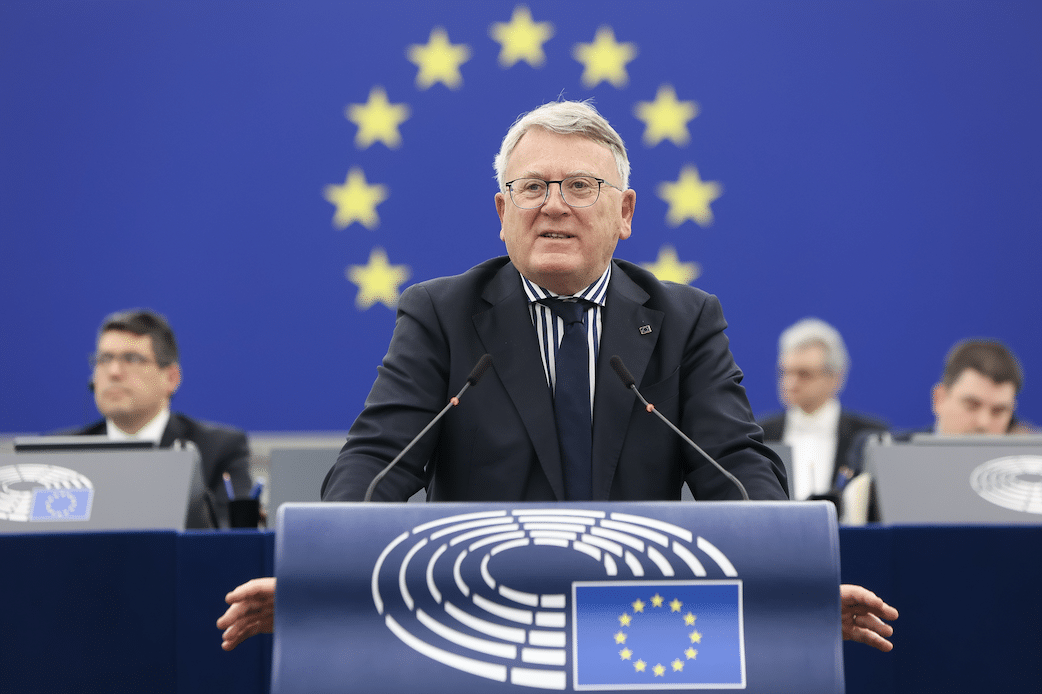

From left: European Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights, Nicolas Schmit, and European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen

Spitzenkandidat—German for “leading candidate”—in European jargon means that political figure that each European party proposes to voters as their first choice for the presidency of the European Commission should they win the EU Parliament elections. Although unofficially, the Socialist one is the first Spitzekandidat of a European party whose name is known in the 2024 election race. The European Greens will choose their own at the Congress in Lyon on Feb. 2-4, The Left at the Congress in Ljubljana on Feb. 23-24, the intentions of the liberals of Renew Europe are still unclear in this regard, and the European People’s Party will hold its Congress in Bucharest on March 6-7. While the choice of Ursula von der Leyen about whether she will run for a second term as commission chair is still unclear (which would imply a move as Spitzenkandidat of the EPP), European Socialists also have the presidency of the European Council in their sights, the race being more hectic after the step back on Jan. 6 by the institution’s current number one, Charles Michel. The strongest name on which the ESP could focus is that of the Danish premier, Mette Frederiksen, but also in the running would be the Spanish counterpart, Pedro Sánchez, and the Portuguese one, António Costa.

The figure of the Spitzenkandidat

The figure of the Spitzenkandidat was first introduced for the 2014 European elections, in the wake of the increased powers that the EU Parliament was given by the Lisbon Treaty—signed in 2007 and entered into force in 2009—and which MEPs wanted to interpret as broadly as possible.

The parties also wanted to try to draw closer to the voters,

who have long considered the commission as a remote organization with broad

powers to influence their lives. Naming a person means making sure that voters can get to know him or her before taking up an important office, and at the same time, it is also a chance for the parties to implicitly suggest who they would like to prevent—even internally—from being chosen after the elections. Because neither the parties nor the parliament formally designate the President of the Commission. Under the Lisbon Treaty, this power rests with the governments, meeting in the European Council, who choose the person who is to lead the Commission. The name is proposed to the European Parliament, which, however, has the power to approve the choice or not. In essence, it is a shared power, between an institution that chooses and an institution that approves. That is why the possible short circuit between the council and parliament can be solved by the introduction of the Spitzenkandidat, but only on the strictly political level, because on the legal one the indication by the parties before the elections has no value. Added to this is the fact that no group in the European Parliament—under current conditions and likely even post-election in June—has the strength to choose the president of the Commission on its own, which is therefore the result of an agreement between different political forces and with national governments.