Brussels – The EU has never been such a target of disinformation. Nor has it ever been so afraid of it. A senior EU official sounded the alarm: “We see a noticeable increase in both the quantity and quality of these campaigns.” With the European elections less than a month away, Brussels has deployed its bodyguards: the European External Action Service in the forefront, but also the Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) and entry into force of the Digital Services Act, the European law regulating the management and removal of illegal content online.

“There is a risk, and we want to be prepared,” the source explains. The threat has a name and a surname: it is the Kremlin’s propaganda machine, the main disinformation actor, according to EU intelligence. Just today (May 15), the ambassadors of the 27 member countries approved new sanctions against four Russian media in light of their disinformation activities. These are reportedly the Voice of Europe, Ria Novosti, Izvestia, and Russia Gazeta, joining 14 others affected by broadcast bans (including cable, satellite, Internet Protocol TV, platforms, websites and apps) and suspension of licenses in member countries. Some EU states, however, don’t have implemented the sanctions yet, not even those decided against Sputnik and Russia Today in the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine.

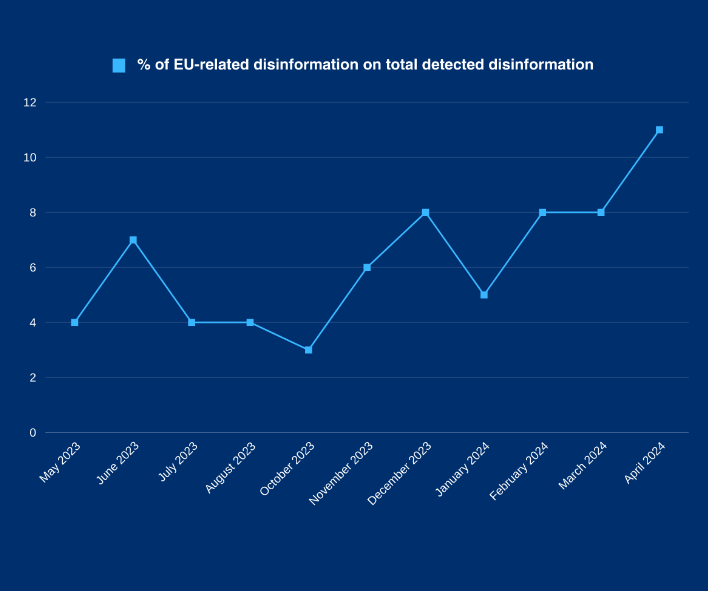

Although preventive actions taken by the EU suggest otherwise, “we do not assume, at least from today’s indicators, that there will be such a massive information manipulation campaign for the elections,” the source further explains. The fact remains that the EU Digital Media Observatory has found, from January onward, a growing trend in disinformation related to EU policies or its institutions. In April, according to Edmo, it amounted to 11 per cent of total detected disinformation, “the highest value for EU-related disinformation since our dedicated monitoring began in May 2023.”

In recent years, the EEAS reportedly identified more than 17 thousand cases of misinformation, a “growing trend,” but “only the tip of the iceberg” because “the more you look, the more you find.” In general terms, disinformation campaigns “are never built on a totally invented issue” but “exploit an existing debate” and “internal discontent.” Indeed, the most frequently used narratives are those related to Ukraine, climate, migration, and the LGBTQI+ community. And “we expect them to increase in the coming days.”

The problem is that, along with the EU’s ability to detect information manipulation campaigns, “techniques have also improved for disinformers. Who are increasingly using more powerful tools such as artificial intelligence” and launching cross-campaigns “simultaneously on multiple platforms.” One example is the Russian-influenced operation unmasked back in May 2022, codenamed Doppelganger, which consisted of cloning several authentic media websites—including Build, Ansa, and The Guardian—on which to offer articles, videos, and generally fake news. Edmo’s investigations also revealed the affair of “Pravda” domains, activated within a week in 19 member countries and in Spanish, English, German, French, Czech, and Italian. A network of coordinated publications always using the same type of sources, the Moscow-controlled news agencies.

The European Commission has also raised the alert to the highest level, building its policy against disinformation on three pillars: in addition to Edmo, there is a code of practice on disinformation currently signed by 44 stakeholders, including online platforms, trade associations, and advertising industry players, and most importantly, since February the EU Digital Services Act has come into force which deals not only with possible foreign influences but with all “systemic risks.”

English version by the Translation Service of Withub