Brussels – It is a historic vote, restoring – if not justice – at least dignity to the thousands of victims and survivors of one of the bloodiest massacres on European soil since World War II, before those carried out by the Russian military in Ukraine. The UN General Assembly, last night (May 23), adopted a resolution establishing July 11 as the International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the Srebrenica Genocide, with 84 countries in favor, 19 against. and 68 abstaining (in addition to 22 who did not vote). But the issue turned out to be much more political than expected, not so much because of the announced campaign of obstructionism and demonization waged by Serbia and Russia with the tacit backing of China, but more because of the repercussions of the vote of individual EU member countries.

The resolution, proposed by Germany and Rwanda and co-sponsored by more than 30 UN members (including all former Yugoslav countries except Serbia and Montenegro), stipulates that “every year,” an international day of remembrance of the Srebrenica genocide will be observed on July 11. In July 1995, at least 8,372 Bosnian civilians -all male, ethnic Muslims – were massacred by the Bosnian Serb forces of Ratko Mladić (not coincidentally referred to as ‘the butcher of Bosnia’) near the enclave of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia. It has been nearly 30 years since that massacre – the largest in terms of casualties in a few days – of a genocide that lasted three and a half years, from April 1992 to the Dayton Accords of December 14, 1995. “The resolution underscores the role of international tribunals in combating impunity and ensuring accountability for genocide,” Germany’s permanent representative to the United Nations, Antje Leendertse, said, pointing out that “it is not against any country, but against those who perpetrated the genocide.”

The resolution, proposed by Germany and Rwanda and co-sponsored by more than 30 UN members (including all former Yugoslav countries except Serbia and Montenegro), stipulates that “every year,” an international day of remembrance of the Srebrenica genocide will be observed on July 11. In July 1995, at least 8,372 Bosnian civilians -all male, ethnic Muslims – were massacred by the Bosnian Serb forces of Ratko Mladić (not coincidentally referred to as ‘the butcher of Bosnia’) near the enclave of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia. It has been nearly 30 years since that massacre – the largest in terms of casualties in a few days – of a genocide that lasted three and a half years, from April 1992 to the Dayton Accords of December 14, 1995. “The resolution underscores the role of international tribunals in combating impunity and ensuring accountability for genocide,” Germany’s permanent representative to the United Nations, Antje Leendertse, said, pointing out that “it is not against any country, but against those who perpetrated the genocide.”

Yet that did not stop Serbia’s president, Aleksandar Vučić, from calling the resolution “highly politicized” and threatening that it “will open Pandora’s box,” particularly in terms of the separatism of the president and ally of Republika Srpska (the Serb-majority entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina), Milorad Dodik. During the vote at the UN General Assembly, the Serbian leader wrapped himself in a Serbian flag, an even more striking gesture to oppose a document that “condemns without reservation” any denial of the Srebrenica genocide as a historical event, as well as “actions that glorify those convicted of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide by international courts,” and calling on all member states to develop “appropriate programs” including in educational systems “to prevent denial and distortion and the occurrence of genocide in the future.”

However, the vote also impacted the European Union, given how the 27 member countries took sides. The abstention of Greece and Slovakia, and, more importantly, the opposition of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, Serbia’s (and Republika Srpska’s) biggest ally throughout the Union, spoiled the united front in support of the resolution. “We don’t comment on the vote of individual member countries. The European Union as an entity does not take part in the vote at the UN General Assembly,” European External Action Service (EEAS) spokesman Peter Stano cut short when answering questions from the Brussels press today (May 24). Not least because, as the European Union, “we have a clear position, which we reiterate every year,” meaning that “we reject any denialism, relativization, or doubt about what happened and what has been established even by the International Tribunals.” Two years ago, the film Quo Vadis, Aida?, based on the events that thousands of Bosnian women in Srebrenica saw despite of themselves, received in the hemicycle of the European Parliament the Premio Lux 2022 of the Audience for European Cinema.

The Republika Srpska-Serbia-Hungary front against Srebrenica

The UN vote on the resolution regarding the Srebrenica genocide highlights a broader regional and international scale diplomatic context, which also indirectly involves the European Union. Hungarian Prime Minister Orbán for years has been pursuing a policy of close diplomatic relations with Bosnian Serb Dodik and Serbian President Vučić, who has also always been close to the secessionist aspirations of Republika Srpska. Moreover, the three leaders are united in various ways by at least questionable positions on Russia and international sanctions: from Orbán’s ‘softer’ one (as a member of the EU) to Vučić’s ‘non-aligned’ one to Dodik’s openly opposed one. These rifts within Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Balkan region, and the European Union itself – of which Hungary is the thorn in the side – risk jeopardizing Sarajevo’s path to EU membership, despite the decision of the European Council on March 21 to start accession negotiations.

With Republika Srpska’s secessionist project that began in October 2021, Dodik’s goal is to remove himself from central state control in crucial areas such as the military, the tax system, and the judiciary, more than 20 years after the end of the ethnic war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After the first bill to establish an autonomous Supreme Judicial Council, the project became increasingly concrete in March 2023, with two bills: one to create a register of foreign-funded associations and foundations and the other to reintroduce criminal penalties for defamation. The so-called law on ‘foreign agents’ is similar to the one adopted by Moscow in December 2022 and was passed in late September amid open criticism of Brussels, while amendments to the Criminal Code came into effect in mid-August despite EU condemnation and now include fines of 5 thousand to 20 thousand Bosnian marks (2.550-10,200 euros) if the defamation takes place “through the press, radio, television, or other means of public information, during a public meeting or otherwise.”

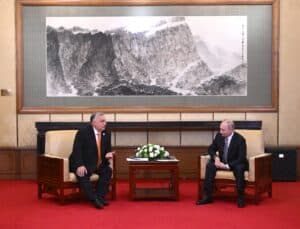

The secessionist provocations were accompanied by the issue of the relationship with Russia after it invaded Ukraine. As early as September 20, 2022, Dodik traveled to Moscow for a bilateral meeting with Putin after provoking Western partners about the illegal annexation of Russian-occupied Ukrainian regions. Provocations that continued in early January 2023 with the awarding to the Russian autocrat the Order of Republika Srpska (the highest honor of the Serb-majority entity in the Balkan country) – in recognition of “patriotic concern and love” toward Banja Luka’s demands – on the occasion of the National Day of Republika Srpska, an unconstitutional holiday under Bosnian law. As if that were not enough, Dodik traveled again to Moscow on May 23, while in Brussels, perplexities arose over the Union’s failure to respond with sanctions.

In the face of Dodik’s secessionist policies and increasingly explicit closeness to Putin (by no means disguised even by Hungarian PM Orbán), the European Union has had a framework of restrictive measures ready to be applied for over two years. However, as revealed by EU sources to Eunews on several occasions, it is precisely Hungary that does not allow the go-ahead thanks to the power of veto in the Council, precisely because of the close political relationship between the two leaders (plus Vučić) who aspire to see the secessionist project of Republika Srpska realized and who oppose with their historical revisionism the recognition of the Srebrenica genocide.

Find more insights on the Balkan region in the BarBalkans newsletter hosted by Eunews

English version by the Translation Service of Withub