Brussels – Northern Kosovo is always a sensitive place for European Union policies, and Schengen visas are no exception. Just a few months after visa liberalization for Kosovar citizens took effect – after a wait of more than five years – the Council of the European Union decided today (July 22) to give the green light to the Regulation removing the exclusion for holders of Serbian passports issued by the Serbian Coordination Directorate, or the directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Belgrade that is responsible for issuing Serbian passports to citizens (of the Serbian ethnic minority) residing in the country that unilaterally declared independence from Belgrade itself in 2008.

Today’s green light “ensures that the entire Western Balkans region will be subject to the same visa regime,” reads the statement of the EU institution, thus concluding the legislative process initiated in November last year by the EU Commission. The Regulation will enter into force on the 20th day after its publication in the Official Journal of the EU and apply in all member states.

Since December 2009, Serbian passport holders had no visa requirements for travel to the Schengen area, except, until now, those who held one issued by the authority established as part of the EU dialogue on visa liberalization with Serbia. However, controversy will not be long in coming in Pristina over the fact that, with this measure, some residents of Kosovo will not need passports issued by the central authorities in Pristina (which, from January 1, 2024, guaranteed the same right to travel without a visa), but will be able to continue to refer to Belgrade and question national sovereignty at a historical moment that is especially sensitive for the two Balkan countries.

What Schengen visa liberalization means

In practice, visa liberalization for a non-EU country means exemption from having to apply for a visa to enter the Schengen area, i.e., the area that has abolished internal borders. Nationals of these states can use their national passports – with no additional requirements – to travel and stay for up to 90 days (in a total period of 180 days) in the EU and Schengen countries.

All citizens of EU member countries can freely cross internal borders with their ID cards – even those outside the Schengen area, namely Cyprus, Bulgaria, Ireland, and Romania – as well as citizens of the external territories belonging to the 27 Schengen countries (Greenland, Svalbard Islands, French Guiana, New Caledonia, and other overseas territories). Also joining the area that abolished internal borders are four non-EU states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. Citizens of any other country usually must apply for a visa (work, tourist, study), which is the act by which a state grants a foreign individual permission to enter its territory. However, the EU has established a shared visa policy for short stays, transit through the territory, or in international airports of Schengen states.

Based on a case-by-case assessment, the Commission may propose to the co-legislators of the EU Parliament and Council a decision to liberalize Schengen visas. The assessment is based on a set of pre-established criteria: irregular migration, public order and security, economic benefits (tourism and foreign trade), human rights, fundamental freedoms, regional coherence implications, and reciprocity. New exemption decisions must be adopted by both co-legislators after bilateral negotiations with the country concerned. Here is the list of countries granted Schengen visa liberalization.

Tensions in northern Kosovo

More than a year has passed since the first event that kicked off one of the most complex and violent phases of relations between Serbia and Kosovo. On May 26, 2023, mass protests broke out after newly elected mayors of Zubin Potok, Zvečan, Leposavić, and Kosovska Mitrovica took office, turning, within three days, into a guerrilla warfare that also involved soldiers from the NATO-led international KFOR mission. Tensions erupted over the Pristina government’s decision to deploy special police forces to allow the mayors elected on April 23 into municipalities in a controversial election round due to the low voter turnout.

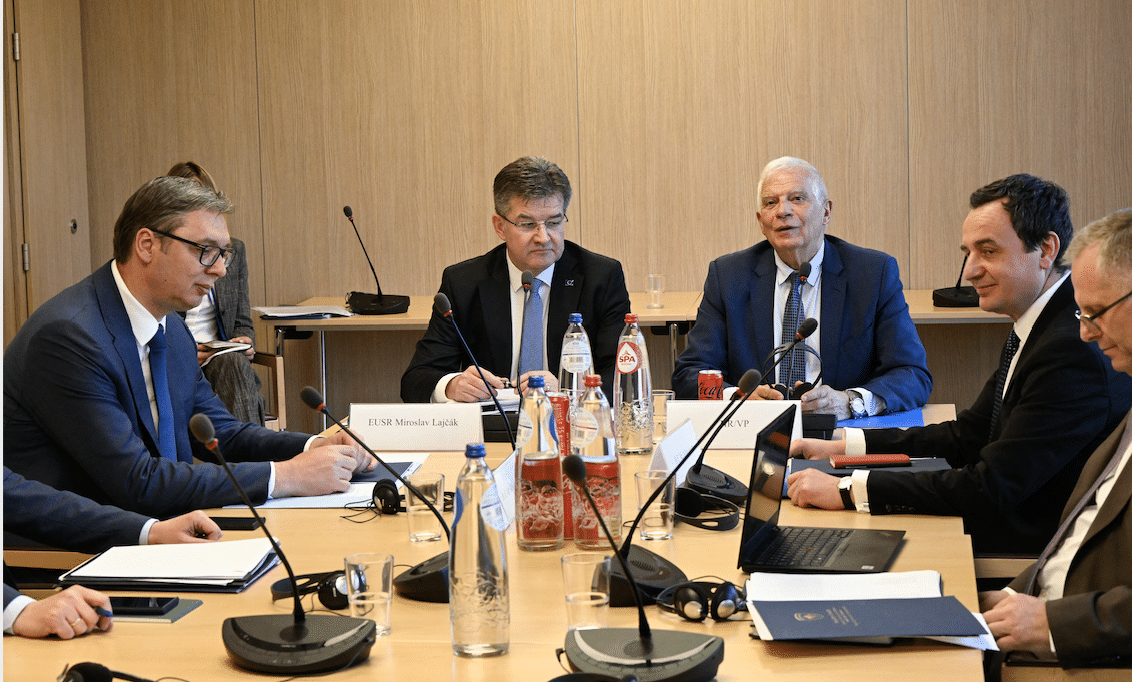

Meanwhile, on June 14, Serbian security services arrested/kidnapped three Kosovar police officers, with the governments of Pristina and Belgrade accusing their respective law enforcement agencies of trespassing. Brussels convened an emergency meeting with the Kosovar premier, Albin Kurti, and the Serbian President, Aleksandar Vučić, to get out of “crisis management mode.”The release of the three Kosovar police officers took place only on June 22. However, due to Pristina’s failure to take a “constructive attitude” to de-escalate the tension, Brussels imposed in late June “temporary and reversible” measures against Kosovo (still in place, despite the roadmap agreed on July 12). The situation escalated with the terrorist attack on September 24 near the Serbian Orthodox monastery in Banjska. On the day of clashes between the Kosovo Police and a group of about 30 gunmen, a policeman and three attackers were killed.

Developments in the attack showed clear branches in neighboring Serbia. The bombers outside the monastery included Milan Radoičić, deputy head of Lista Srpska – as he confirmed a few days after the armed attack – as well as Milorad Jevtić, a close associate of the Serbian President’s son, Danilo Vučić. A Serbian “major military deployment” along the administrative border reported by the United States worsened the situation. The threat did not materialize, but the EU began to mull the possibility of imposing the same measures in force against Pristina against Belgrade. But the green light needed unanimity in the Council, and Vučić’s closest ally inside the Union-the Hungarian premier, Viktor Orbán – vetoed. As if that were not enough, before early elections in Serbia on December 17, the last act of the government led by Ana Brnabić was to send a letter to Brussels to warn that Serbian institutions do not recognize the legal value of the verbal commitments made in the context of the Pristina-Belgrade dialogue and that they did not recognize the de facto sovereignty of Kosovo.

The only positive news, at the moment, is the resolution of the ‘battle of the license plates’ between Serbia and Kosovo, thanks to the decision between late 2023 and early 2024 on the mutual recognition for vehicles entering the border: even given this year’s unpromising assumptions. With the entry into force of the Regulation on Transparency and Stability of Financial Flows and Combating Money Laundering and Counterfeiting, as of Feb. 1, the euro became the sole currency of exchange and deposit in bank accounts: the Serbian dinar can still be exchanged on a par with the Albanian lek or the dollar, but the decision will impact all those public services that never adjusted to Pristina’s adoption of the euro in 2002 (even before independence). On Feb. 5, the special police operations at the offices of the temporary institutions run by Serbia in four municipalities in northern Kosovo (Dragash, Pejë, Istog and Klinë) and at the headquarters of the NGO Center For Peace and Tolerance in Pristina raised controversy in Brussels: since 2008 Belgrade has continued to fund municipalities, companies, public enterprises, kindergartens, schools, public universities, and hospitals available to the Serb minority, illegally according to the Kosovo Constitution.

The only positive news, at the moment, is the resolution of the ‘battle of the license plates’ between Serbia and Kosovo, thanks to the decision between late 2023 and early 2024 on the mutual recognition for vehicles entering the border: even given this year’s unpromising assumptions. With the entry into force of the Regulation on Transparency and Stability of Financial Flows and Combating Money Laundering and Counterfeiting, as of Feb. 1, the euro became the sole currency of exchange and deposit in bank accounts: the Serbian dinar can still be exchanged on a par with the Albanian lek or the dollar, but the decision will impact all those public services that never adjusted to Pristina’s adoption of the euro in 2002 (even before independence). On Feb. 5, the special police operations at the offices of the temporary institutions run by Serbia in four municipalities in northern Kosovo (Dragash, Pejë, Istog and Klinë) and at the headquarters of the NGO Center For Peace and Tolerance in Pristina raised controversy in Brussels: since 2008 Belgrade has continued to fund municipalities, companies, public enterprises, kindergartens, schools, public universities, and hospitals available to the Serb minority, illegally according to the Kosovo Constitution.

Find more insights on the Balkan region in the BarBalkans newsletter hosted by Eunews

English version by the Translation Service of Withub